Prospective Intentionality and Time Management

““If you will pay close heed to the problem, you will find that the largest portion of our life passes while we are doing ill, a goodly share while we are doing nothing, and the whole while we are doing that which is not to the purpose.””

We strive to manage our time in the most efficient manner possible. We boast about our shiny new time management techniques and tools with our interlocutors, attempting to increase our hierarchical position in the eyes of others, in an endless signaling game. All of this while often being self conscious of, or even deeply uncomfortable with, our own life purpose and trajectory. Time seems to be an obsession, and particularly so in the knowledge work paradigm. Hours spent in meetings whose true objective no one really understands, but everyone silently subscribes to, in an effort to mitigate the existential dread of not knowing one's place in life, at any given moment. In Seneca's moral letters to Lucilus, the Stoic philosopher underlines the time-wasting characteristic of our life, almost addressing what today has become widely known as procrastination. Procrastination corresponds to deviating one's behavior from what is essential in our life, by postponing or avoiding it. We are aware, somewhere inside of us, that doing what is essential would be a good idea. And yet, we cannot resist, or so we convince ourselves, the endless competing possibilities life provides us with. At times, we do not even know what is the essential, or the direction of our existence.

Are we sure that time exists in the first place? Physicist Carlo Rovelli has a lot to say about that, and he also wrote a book about it. Time seems to manifest itself in a relativistic entanglement between the past and the future.

“I suspect that what we call the “flowing” of time has to be understood by studying the structure of our brain rather than by studying physics: evolution has shaped our brain into a machine that feeds off memory in order to anticipate the future.”

In any case, we cannot seem to escape the inexorable use of time as a conventional instrument for individuals to coexist harmoniously in society. When setting up an appointment, we would not want other people to show up late, or not show up at all, merely because time does not exist, at least at this point in time. We are aware and self-conscious of our own use of time. We may decide to allocate a certain amount of time of our day to working, or feel like we are forced to do so, in case we did not set our own priorities straight at some point in life, so to be responsible for our own endeavors while drawing a sense of fulfillment from them. We may make decisions merely because of fear of failure, or gripping anxiety. Fear of being conscious of failing often puts brakes on what we do with our own time. When doing so, we are anxiously attending to the future, falling prey to cognitive distortions and the biased nature of our own mind. Time is a conventional tool in society. Imagine not having time and attempting to set an appointment, or a work meeting. In such a case, we may use relative description that provide a different depiction of time, such as "when the sun is setting", hence anchoring time to external, out-of-control forces that provide a framework of reference to understand the time, although not precisely.

Time and Human Nature

““One must cultivate one’s own garden””

French philosopher Voltaire communicated the importance of cultivating one's own garden in his 1759 novella Candide: Optimism. This corresponds to how we first need to "sort our things out" before going out in the world and contribute to the development of our immediate social groups, and society at large. It is similar to what psychologist Jordan B. Peterson presents as rule number 6 in his book 12 Rules for Life: "set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world". This may seem disconnected from the topic of time management. In fact, the way we use our time is highly dependent on our values, life mission, and vision for the future. Without those elements clear in mind, life becomes a constant quest for order in an otherwise chaotic existence, where reactivity is at the center of time management, as opposed to prospective intentionality. Setting clear values in our life begins with thought experiments and thinking hardly about what is essential for us. I reckon the Future authoring program is a great starting point for that.

As the author of this article from The Guardian postulates, "Time management promised a sense of control in a world in which individuals – decreasingly supported by the social bonds of religion or community – seemed to lack it." Personal productivity techniques, although incredibly popular, have seemed to exacerbate the anxiety-ridden human struggle of existence, instead of reducing it. Efficiency techniques themselves become a source of emotional discomfort, hard to keep up with in the long run. It is in this context that the true sources of meaning and effective time management are principles and personal values. That is because these concepts provide us with clear boundaries and intrinsic "rules" that add some constraints to the infinite loop of external triggers in today's age. Constraints, in turn, foster creativity and personal meaning.

Time Blocking and Indistraction

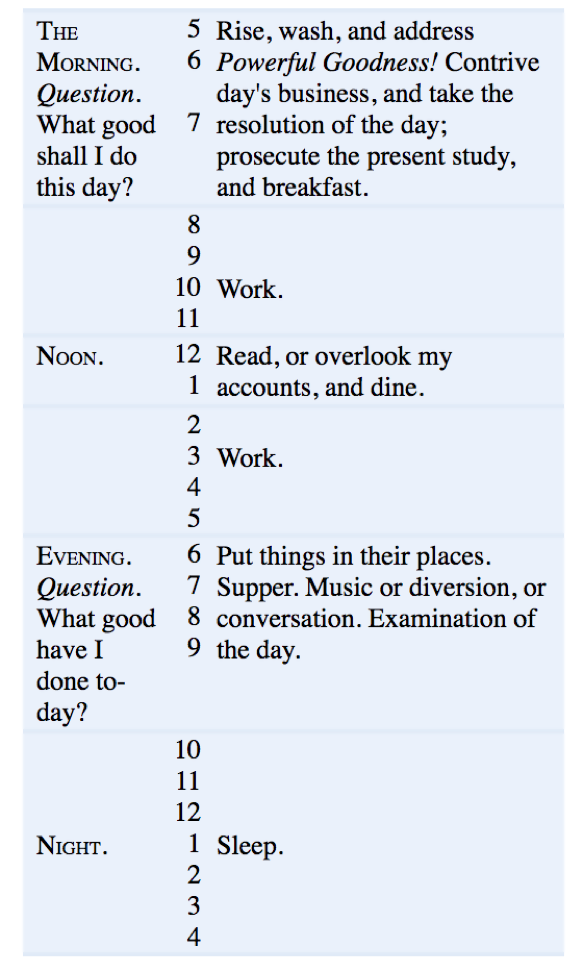

Two ways of managing our time put forward (widespread rather than invented) by author and professor Cal Newport are time blocking and deep work. If our values and essentials are well defined in our mind, we can set a direction that drives us toward our purpose in life. Time blocking is nothing revolutionary. It is probably an image from Benjamin Franklin the oldest repertoire available on time blocking. Time blocking is the practice of intentionally allocating specific time periods to doing the things we most value in life at any given moment, with intentionality and presence.

When paired with deep work (getting in the flow state, or working fully immersed on something for a defined period of time), time blocking can unleash a well-structured and purpose-driven approach to living. This, in turn, may prevent what Seneca defines as "the whole while we are doing that which is not the purpose".

The concept of time blocking and the deep life is also touched upon by Nir Eyal in this conversation, as well as his book Indistractable. Indistraction is the ability to let go of the endless number of inputs coming from externally, especially due to technological tools out of our immediate control. By mastering the art of indistraction we can attend to what is truly essential in our life; something Greg McKeown talks extensively about in his book Essentialism. As author Nir Eyal puts it: "time management requires pain management". Human beings strive to avoid discomfort. In order to conquer our time we need to first learn to deal with our emotional reactions, which we often label as positive or negative. In fact, emotions are mere states of being, sometimes stemming from distorted thinking, which we are all subject to, although to differing degrees. As Nir Eyal points out, the opposite of distraction is traction. Traction is what pulls us closer to where we are directed in life, driven by priorities and values.

““A mistake repeated more than once is a decision.””

Balancing Presence and Planning

Dealing with emotional reactions calls for a mindful approach to existence, which is rooted in the present moment while aware of the relevance of the past and future. Anxiety stems from fear of the unknown in the future. It is the byproduct of excessive perceived chaos. Accepting the present moment while planning our time carefully may represent a sweet spot for great achievements. We can plan for the future while rooted in the present moment, which is only possible through an understanding of the human mind and how to deal with emotional reactions. We can look at the future as a set of events that is going to unfold at some point, and for which we want to be prepared in advance, without attaching our self worth to it. This also relates to the Stoic mantra of the dichotomy of control (some things are under our control, some things are not). The present moment is controllable to a great extent. The future can only be imagined with all the information available in the present. The lack of perceived order in the outlook of the future scares us.

An Intentional Approach to Time Management

To conclude, the concept of time management entails much more than mere surface-level productivity techniques. These may result useful to some degree in the short term. But they do not intervene on the root cause of the dreadful feeling of aimlessness in our life we sometimes experience. Prospective intentionality begins with setting our principles and values straight upfront, in order to deeply understand our own priorities, attend to them religiously, and live a more examined life, in which time management is a mere by-product of our higher purpose.

I also write a weekly newsletter: Weekly Reflection. You can check out previous issues and sign up here.

RESOURCES

How Do I Balance Presence and Planning? | Eckhart Tolle

How to Save the World (or at least yourself) from Bad Meetings | David Grady

The 7 Minutes a Day You Need to Master to Be Truly Productive | James Clear

Mastering Indistraction | Nir Eyal

SIMILAR ARTICLES