“A Universe of Atoms, an Atom in the Universe”

"I don't know."

Such a tough sentence to utter, especially when under social pressure from peers, or from a person whom we want to please, when in a conversation.

Being aware of one's own knowledge is not an easy thing. The knowledge we perceive to have on a certain subject is called metacognition. This is the awareness of the things we actually know, as well as of our blindspots, which we all have plenty of. As it turns out, having a decent level of awareness about our own knowledge is not such an easy business. In fact, distortions are the norm when it comes to metacognition. We all perceive ourselves to be more knowledgeable than we actually are in something. Everyone has been there at least once in their life. And the real issue is: we do not seem capable of addressing our lack of knowledge most of the times, especially when in social situations that may pressure us to feel part of a group, or to be "the expert" in a small group of people (in which case you don't want to let people down, do you?).

Welcome to the infinite world of the Dunning Kruger effect, the cognitive bias responsible for our lack of metacognition and willingness to challenge our beliefs and ideas.

"We are all confident idiots", states the title of an article written by David Dunning on the Pacific Standard in 2017.

You may be thinking: Who are you? And why are you calling me an idiot?

Well, David Dunning, as you may recognize from the surname, is one of the psychologists who, back in 1999, came up with the Dunning Kruger effect, after publishing the paper "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". At that time, Justin Kruger (the other researcher discovering this cognitive bias) was a graduate student of Dr. Dunning, and the paper was co-authored by the two.

"[. . .] in many areas of life, incompetent people do not recognize—scratch that, cannot recognize—just how incompetent they are, a phenomenon that has come to be known as the Dunning-Kruger effect." - from the article We are all confident idiots by Dr. Dunning.-

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which people with low ability on a task overestimate their ability. And within the group of 'people' there is also you, and me. We often times are good at depicting other people's lack of knowledge and ability, but we usually fail to address the same pitfalls in ourselves. So, being aware of the Dunning-Kruger bias can be the first step towards a higher level of metacognition and self-consciousness.

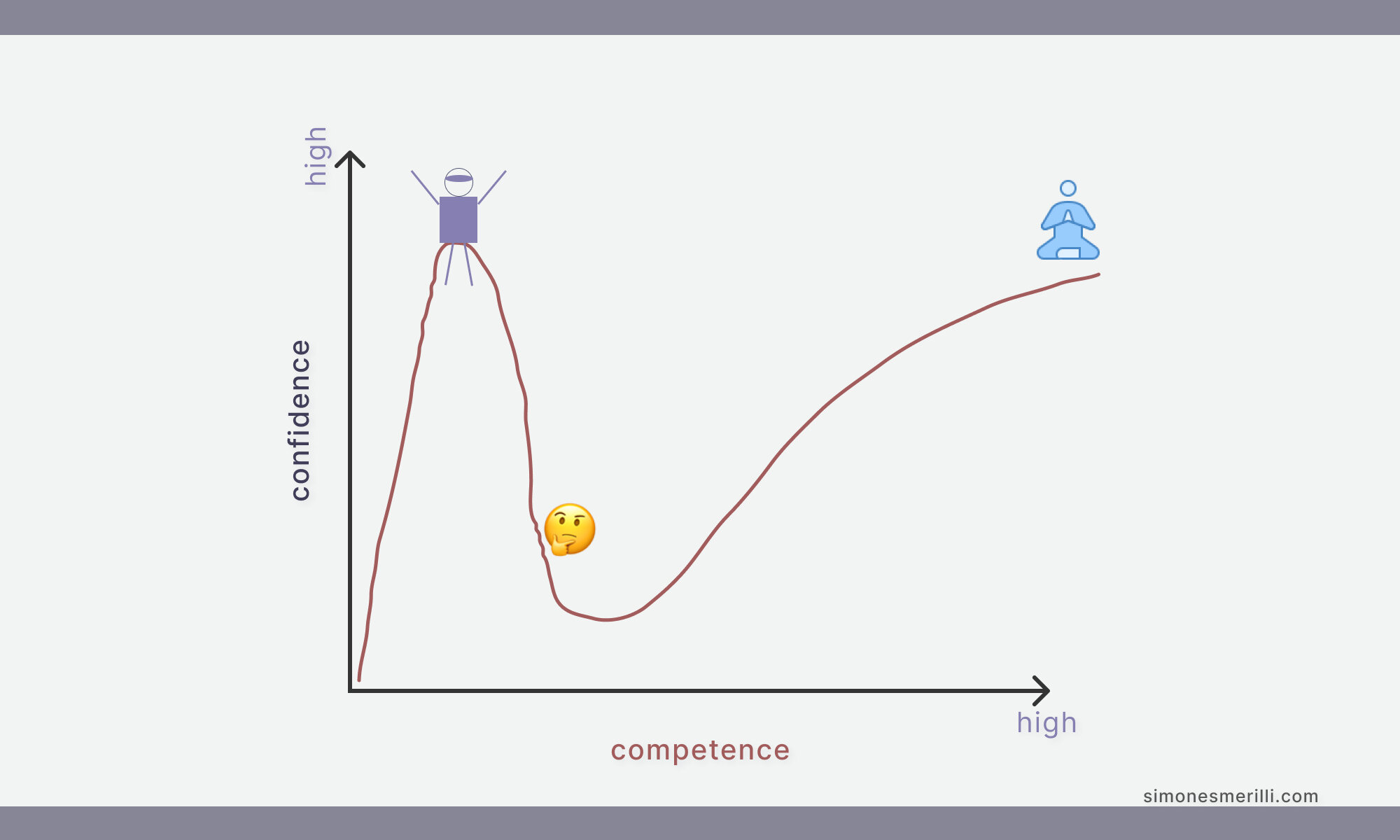

There is a graph depicting the knowledge-confidence relation over time, and it clearly shows how as soon as we go from knowing nothing to being aware of something in a certain topic or skill, our level of perceived ability skyrockets, to then plummet as we dig deeper into the subject at hand. This can be explained by a simple reality: usually, every area of our life (whether it be an academic subject such as physics and math, or a skill such as playing the guitar or coding) has many layers of knowledge or ability to go through in order to become decent at it. However, acknowledging this seems very difficult, and an increase in knowledge from 0 to 0.1 is perceived as a giant leap by our monkey brain. What then happens over time, however, is that this metacognition of how many nuances there are in a subject becomes more clear to us as we get deeper into practicing the thing. And so we fall into existential crisis mode, where we actually have a decent amount of ability but we are aware of how many things we do not know. Being humble to criticism and keeping pushing forward is likely the way to expertise.

Dunning Kruger Effect in Studying

As a university student in this moment of my life, becoming aware of this distortion of reality has made me think about how the Dunning Kruger effect applies to studying in school, and you can often see it at play in classrooms before an exam. I really like this video by Unjaded Jade on this.

It happens all the time. The students who study properly (by properly I mean grasping the meaning of the subject and its components - not necessarily equal to spending a lot of time trying to memorize things) feel more insecure about what they know compared to those students who studied little. And if you enter in a room full of students ready to take an exam you can sense it by listening to the conversations in which groups of people are trying to exchange information about the subject among each other so to test their knowledge and acquire some from others. And you can especially notice the Dunning-Kruger effect when a student who says that "she/he knows nothing" ends up getting a very high mark on the exam. Metacognition at play right there.

For us students, being aware of the role of the Dunning-Kruger effect implies that if we study a lot and feel insecure about our knowledge, but we test ourselves using active recall and we are able to answer most of the questions right, that's probably our mind playing a game on us. Which does not mean that we are experts on something just by studying it for an exam. But it does probably mean that we are actually sufficiently prepared to take the exam and pass it successfully.

Working Around the Dunning-Kruger Bias

The Dunning-Kruger effect is powerful and deeply ingrained in our minds. Becoming aware of its existence is the first step towards trying to figure out the correct thinking pattern and behaviour to implement in order to not fall prey to it. But knowing the existence of the Dunning-Kruger effect does not make us experts on taming it and recognizing our own ignorance. In his long article, Dunning offers some practical advice to "see through the clutter" and eradicate the power of this bias as much as possible.

Be your own devil's advocate.

Question your thoughts and beliefs, think of counter arguments to your views, criticize your logic. Having a person whose main task is to criticize and question a group's logic is one of the main things behavioral psychologists recommend doing when working in groups to a project. Being your own devil's advocate (or having a specific person appointed for this job in a group) makes discussions uncomfortable and prolonged. However, the final decisions tend to be more grounded and accurate if we think through them critically and with an open mind.

Seek Advice.

Although everyone is victim of the Dunning Kruger effect, talking to other people who are more knowledgeable than you in the field you are interested in, or have more experience than you, may help you to get rid of misconceptions. As Prof. Dunning puts it in his article, "a discussion can often be sufficient to rid a serious person of his or her most egregious misconceptions."

Reason by first principles as much as possible.

This is actually my own "suggestion". First principle thinking is what makes great people and scientists stand out from the crowd. Have an open mind, be eager to discover the truth, not to be right in a discussion. Reasoning by first principles means dissecting an argument or subject in small pieces beginning to analyse it from the very first theory behind it. This certainly requires a lot of cognitive effort and practice, but it can do wonders for actually seeing things clearly for what they are, not for what other people perceive they are (the latter being reasoning by analogy). For a great article about first principle thinking, read this one by Wait but Why, or this by James Clear.

I’ll leave you with a sentence by Prof. Dunning himself (from "We are all confident idiots"):

The built-in features of our brains, and the life experiences we accumulate, do in fact fill our heads with immense knowledge; what they do not confer is insight into the dimensions of our ignorance. As such, wisdom may not involve facts and formulas so much as the ability to recognize when a limit has been reached. Stumbling through all our cognitive clutter just to recognize a true “I don’t know” may not constitute failure as much as it does an enviable success, a crucial signpost that shows us we are traveling in the right direction toward the truth.

If you enjoyed this post, here are some similar articles you may find interesting:

FURTHER READING & RESOURCES

Sign Up to the Email Newsletter and get new posts delivered to your inbox as soon as they are published.