Conflict Management and Effective Confrontation

Often, we’re not arguing about what we think we’re arguing about. Conflict is an inherent part of work or personal life. Although often considered uncomfortable and avoidable at all costs by many of us (especially if you score high in agreeableness), how we manage conflict makes the difference, as opposed to how often we enter into conflict. Agreeing to disagree, as organizational psychologist Adam Grant points out, is not a valuable option to resolve conflict. It is, on the other hand, a possible defense mechanism to end the conflict as soon as possible and avoid the true, real elephant in the room, or the brain. For conflict to exist, there must be a perception of conflict between the parties involved. Conflict can arise from a clash of personalities, attitudes, circumstances. Our ego-driven brains often forget about getting to what's true as opposed to pursuing "being right." Every individual is capable of good and evil. There is this seemingly constant tension within each of us. Learning, practicing, and adopting a process-oriented, calm mindset in life can make a difference when it comes to handling conflict. Do you want to be focused on yourself and how right you are in the face of society and your ingroup? Isn't it a better idea to maybe pursue getting as close to the truth as possible in life and conflict alike? I believe this quote from psychologist Carl Gustav Jung points to a much-needed realization, especially in the context of conflict:

““Physical” is not the only criterion of truth: there are also psychic truths which can neither be explained nor proved or contested in any physical way.”

The Types of Conflict

As organizational psychologist Adam Grant and his guests point out in this podcast episode, there are 3 main types of conflict:

Task-related conflict: this often takes place at work, and is often the most healthy nature of conflict, since it is based on a specific external object, or task, whose boundaries and characteristics may not be that clear within a group or individuals.

Relationship conflict: this category of conflict is all about clashing personalities and egos. Relationship conflict is the kind of conflict that can often be seen within families, or within clashing colleagues at work. This type of dispute has the characteristic of being highly driven by the ego of conflicting people. All too often, relationship conflict and task conflict get blurred and become potentially destructive battles. The key to resolving relationship conflict is to increase self-awareness and the awareness of the other party involved at the same time. Personality traits cannot be changed, at least in the short run. Hence, working on honing our attitudes toward conflict and relationships is what truly makes the difference in this scenario.

Status conflict: "Status conflict is about where we fit in the hierarchy that we're in together. So I think I'm higher in this informal status hierarchy than you. And you think you're higher in this informal status hierarchy than me or we're equal, but you're acting like you're higher" (CORINNE BENDERSKY). Clarity of roles and boundaries within the organization or any group is a pivotal deterrent to status conflict, which can often arise if there is no clear understanding of the role each person of a group plays. Another stepping stone to resolve status conflict is establishing a sense of genuine respect for each other. In the words of Bendersky: "that lowers the perception of that interaction is threatening and makes them less defensive and more open to working with the other person and maybe resolving the conflict."

The process of conflict

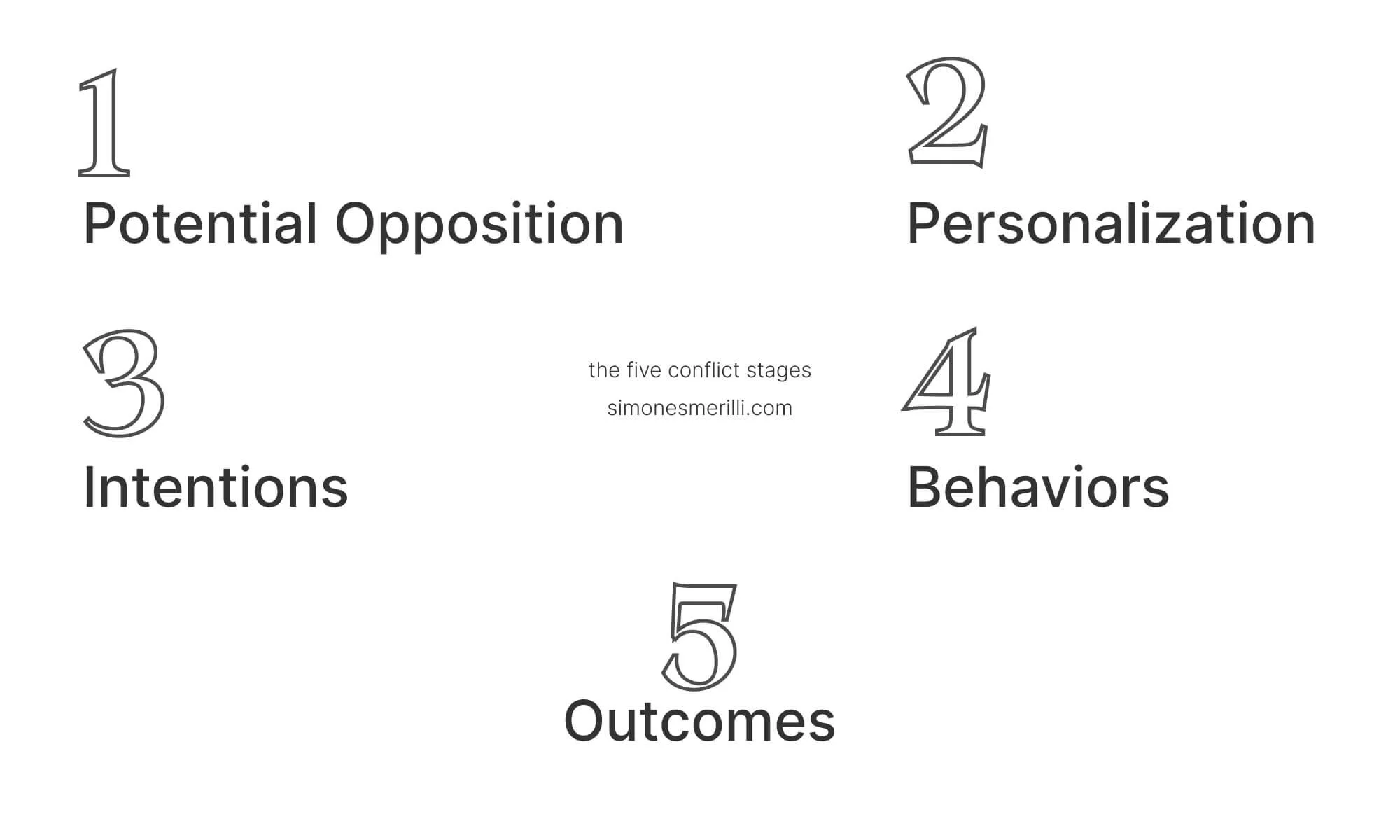

There are five broad stages that characterize conflict

There are 5 main stages defining a conflict process (Robbins and Judge, 2018):

Potential opposition or incompatibility → this stage marks the appearance of conditions that create opportunities for conflict to arise. These conditions can be grouped into 3 general categories: communication (too little or too much is dysfunctional), structure (includes factors such as the size of group, goal*,* compatibility, degree of dependence between groups, reward systems), personal variables (include personality, values, emotions).

Cognition and Personalization → the second stage is where conflict issues become defined. There can be perceived and felt conflict at this point. The former refers to the awareness of the existence of the conflict from one or more parties; the latter is the emotional involvement in the conflict, which sparks anxiety, tension, and "negative" feelings.

Intentions → decisions to act in a certain way (perception → intention → behavior). Conflict-handling intentions fall along 2 dimensions: assertiveness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy his/her own concerns) and cooperativeness (the degree to which one party attempts to satisfy the other party’s concerns).

Behavior → the stage where conflict becomes visible. The intensity of conflict can vary widely, from minor disagreements to overt efforts to "destroy" the other party.

Outcomes → Conflict is functional (constructive) when it "improves the quality of decisions, stimulates creativity and innovation, encourages interest and curiosity, fosters an environment of self-evaluation and change" (Tan, 2020). We can classify conflict as dysfunctional, instead, when it "breeds discontent, reduces group effectiveness and threatens the group's survival" (Tan, 2020).

Cognitive biases in conflict

The expectation gap

Human discontent can be very often attributed to the expectation gap, as Nat Ware concisely explains in his popular Ted Talk. "Our happiness is largely determined by expectations. Expectations are largely determined by what we consider to be normal. And what we consider to be normal is largely based on our imagination, based on others around us, and based on our past. And so we have these constant battles; the battle between our imagination and our reality; the battle between the reality that we experience and what we think or perceive that others experience; the battle between our reality and our past reality." Expecting precise behaviors from the people around us, basing our expectation on our own definition of "good," may easily lead to conflict when we realize that our expectations have simply not been met.

The ladder of inference

Understanding what type of conflict we are taking part in at any given time is the first key milestone to moving toward effective conflict management. Reducing the conflict motive to its deep essence is just as pivotal of a step. The ladder of inference is a very helpful tool here, as Grant posits. According to this ladder, at the bottom of conflict, there are distorted assumptions we make about the other individuals involved. This reminds me of competing commitments. One powerful way to delve deep into the ladder of inference is to let the people involved in the conflict describe their personalities in the process of conflict resolution.

““When someone disappoints you, it’s not because of their actions.

It’s because of a clash between their actions and your expectations.

Understanding their personality can help you rethink your assumptions and conclusions… and adjust your expectations.””

Competing commitments

“A competing commitment is a subconscious, hidden goal that conflicts with our stated commitments.”

This is what Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey write in their HBR article “The Real Reason People Won’t Change”. As we carry out our existence in the social world, whether in the workplace or personal relationships, we often lose track of our authentic self, or maybe completely neglect its existence. However, our true inner motives, whether hidden or not, are still there, somewhere in the background, leading our actions, especially in tough times. Actions speak louder than words. We may behave in specific manners, or resist change, exactly because of some inner friction which we can sense and are deeply aware of, and which we cannot seem to be able to let go, in conscious acceptance. Competing commitments are our own, personal, hidden motives in everyday life, which are grounded on big assumptions - “deeply rooted beliefs about ourselves and the world around us” (Kegan & Lahey, 2001).

““Competing commitments should not be seen as weaknesses. They represent some version of self-protection, a perfectly natural and reasonable human impulse.” ”

Leading tough conversations: a first-principles analysis

Empathy and honesty are at the basis of effective confrontation, as Simon Sinek points out. The FBI method of confrontation serves the purpose of expressing clearly your perceptions of the problem, while framing it in terms of "feelings", as opposed to impulsive perceived facts. You may be wrong in your estimation, and you can only discover how wrong (or not wrong) you are if you lean into the discomfort of confrontation. The FBI method presented by Simon Sinek stands on three pillars: (1) Express your feeling precisely, calmly, and truly wanting to listen; (2) State the specific behavior that made your feeling of anger, resentment, etc. arise (pick one specific instance if the behavior is repeated multiple times); (3) Define the impact that the behavior of the individual has had on you, your surroundings, the people around you, the broad community or organization. Framing problems in terms "I feel", or "It seems to me that" can be powerful. Not because of its persuasive nature. There is nothing persuasive about it. But because of the state of mind this framing can put us (and the other party) in. Something along the lines: "Look, I don't know if this is my cognitive distortion or the absolute truth. What I know for sure, however, is that your specific behavior has provoked an adverse reaction in me, and harboring that reaction inside of me without addressing it is dangerous, very dangerous for our relationship and interactions going forward. So, I think it is a good idea if we address this issue, and I get a bit vulnerable, and you need to pay close attention to what I say, and I will pay close attention to your response, and we can sort this out together, maturely and free from egoic reactivity."

Leaning into effective confrontation can feel incredibly daunting. Especially if you are moderately high in agreeableness, the mere thought of leaning into potential upsetting territory can be frightening. It can be frightening because you don't feel it in your nature to lean into conflict. It feels scary because you need to initiate the "honest talk", which places you in a vulnerable position and takes the predictability out of the equation. Ph.D. Adar Cohen shares three simple yet pivotal mental models (steps) for leading tough conversations in this fantastic Ted Talk.

Move towards the conflict: avoiding addressing the conversation will only keep you scared, resentful, bitter.

You do not know anything or, if you know, pretend you don’t. Be genuinely interested and listen attentively.

Keep quiet: be comfortable in silence. Let the silence lead the conversation. Lean into it. Take the necessary time. Do not rush it. There is no need to rush it. Sorting things out where there is conflict, whatever its scope, is the only thing that matters in the moment. Rushing in to break silence may be a sign of nervousness. It may break the safe environment created until that point, shuttering any good intentions that were set upfront.

It is not a matter of avoiding conflict; it is all about leaning into the discomfort of addressing and managing the conflict.

Ultimately, creating a space where conflict is accepted, demystified, and worked upon very intentionally when it arises is the key to an organization's/group's well-being and effective conflict management.

If you find this article valuable, consider signing up for the "anti-newsletter" Weekly Reflection. One newsletter issue per week containing essential concepts and tools to navigate life deeper than the surface.RESOURCES

The Science of Productive Conflict | Work Life with Adam Grant

Effective Confrontation | Simon Sinek

How to Lead Tough Conversations | Adar Cohen

Why We are Unhappy — The Expectation Gap | Nat Ware

de Wit, F. R. C., Greer, L. L., & Jehn, K. A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 360–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024844

Laursen, B., Finkelstein, B., & Betts, N. (2001). A Developmental Meta-Analysis of Peer Conflict Resolution. Developmental Review, 21(4), 423-449. doi: 10.1006/drev.2000.0531

A meta-analytical review of the relationship between emotional intelligence and leaders’ constructive conflict management - Andrea Schlaerth, Nurcan Ensari, Julie Christian, 2013. (2021). Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1368430212439907